How do photographic images bolster the experience of memory (real or imagined) and what role does our intention—individually or collectively—play in experiencing (or reinterpreting) those memories?

For my final project in WS-372, I look again at the use of photographs in Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home. I welcome Dunye’s compelling case that we should create the archives we need. I share with Bechdel a parent/child collision of sexual identities and a fascination with who our parents might have been before us…or indeed, without us. I explore the power of imagery even decades after we’ve forgotten something. And I look at the work of Ken Gonzales-Day who bookends Dunye’s invented archive by reworking an ugly historical record so we might more thoughtfully engage in the experiences of lives sacrificed to a country that stubbornly refuses to contend with its many brutal legacies.

Which image is real?

The Watermelon Woman:

Creating An Archive

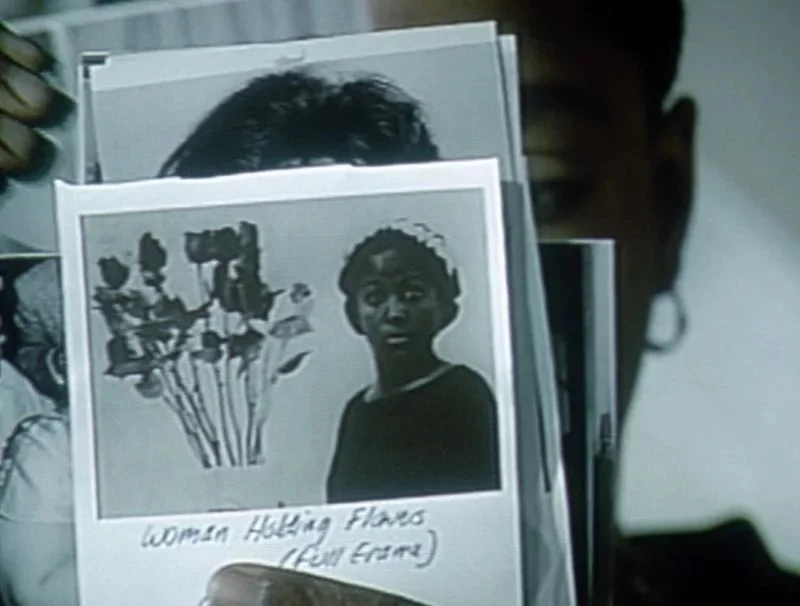

In Cheryl Dunye’s film, The Watermelon Woman (1996), budget constraints required the filmmakers to create an archive (rather than license an existing one), fashioning a life, career, and body of work around the fictional “Fae Richards,” the subject of Cheryl’s documentary film-within-the-film. When Dunye’s Cheryl visits an archive within the movie, she flips through both “created” photos and images from “real” Black Hollywood, including Louise Beavers, Fredi Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, and Juanita Moore among many others. By melding the archival and “archival” images, Dunye’s film is able to convince viewers that what is being documented is “real”. More importantly, Dunye’s film focuses on the lives of Black lesbians for whom documented history is scarce. By inventing an archive for the fictional Fae Richards, Dunye makes clear the importance of recording histories of underrepresented intersectional communities, as in the film’s final epigraph, “Sometimes you have to create your own history.”

Which archive is created?

Fun Home:

Building A Mystery

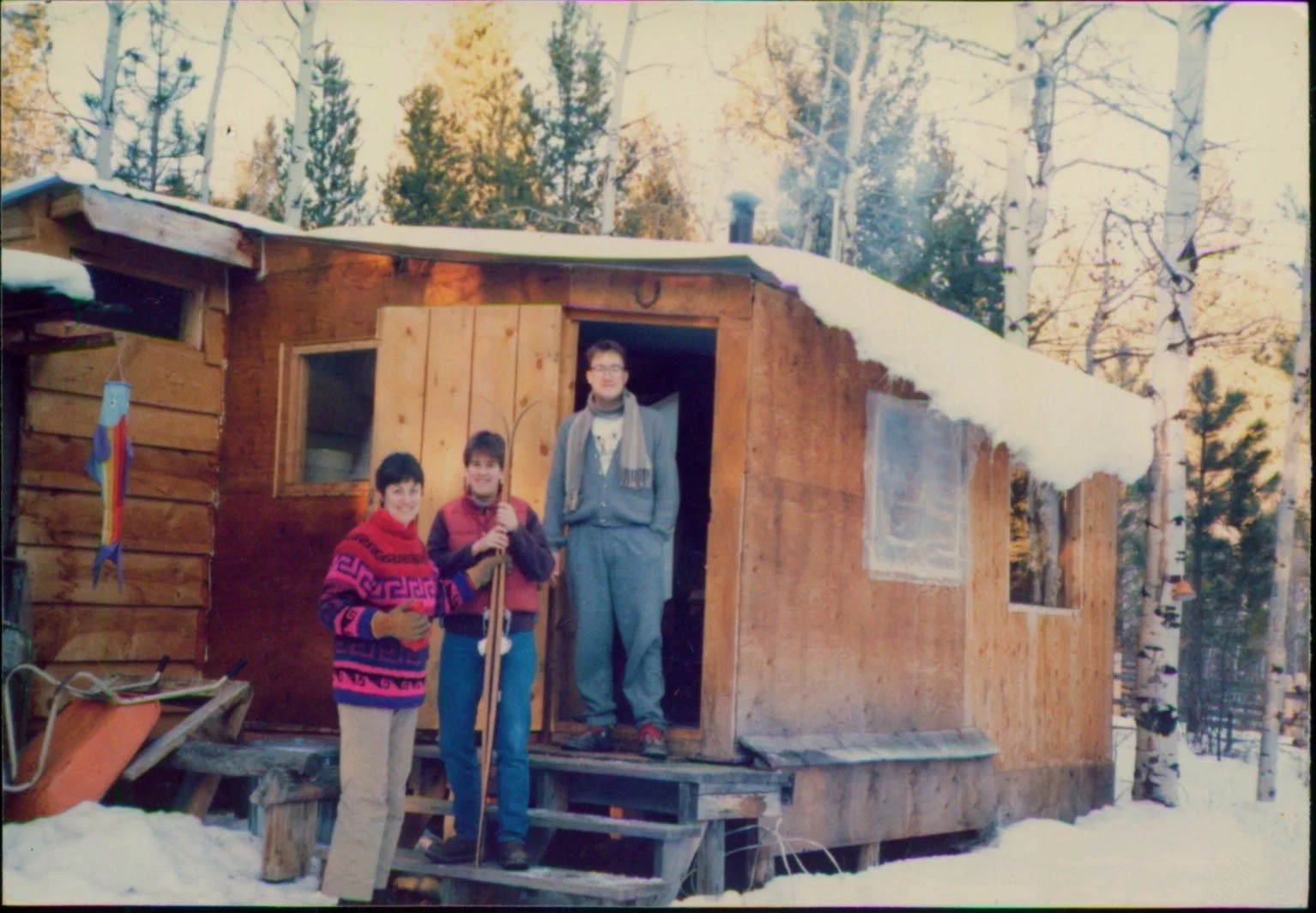

In her memoir, Fun Home (2006), Alison Bechdel confronts difficult, multi-layered traumas involving the death (potential suicide) of one of her parents and the parallels between her own queer life and that of her closeted father. One method of illustration Bechdel uses includes recreating family photographs, as she does here on page 120. At top is a photo of her father in bathing beauty drag, about which she has no context. Beneath it she draws both a photo of her father in his early 20s and a photograph of herself at a similar age. Her captions note the similarities of affect and appearance and wonder if her father’s photo was taken by a lover as her own was.

Gregg Moore, Claire de Loon and Soleca, The Bohemian Goddess (2005).